Written by Glenn Ahrens, Oregon State University

Trees are genetically adapted to local climate. As climate changes, local populations may become maladapted. Because many tree species do not produce seed for several years after establishment, and because multiple generations are required for adaptation to occur, climate is expected to change faster than species or populations can adapt. One potential solution is assisted migration – the deliberate establishment of a new population of a species or genetic type outside its current geographic range.

Assisted migration may save species or ecosystems threatened with extinction or improve forest health, productivity, or resilience by increasing genetic diversity and adaptability within populations. This may involve controlling the genetics of planted trees by selecting the geographic origin of seed sources (within or between species) to improve forest health under anticipated climate scenarios.

With assisted migration to maintain forest health, the goal is to reduce the likelihood that the population of trees on a site will become maladapted under changing climate before reaching maturity (economic or biological, depending on management objectives). Given the genetic diversity within a species and the variability of climate across the range of a tree species, populations (not species) are the logical management unit when considering assisted migration.

Aggressive approaches to assisted migration are highly debated among scientists and conservationists. Aggressive approaches would involve choosing a future climate scenario and selecting species and/or genetic types that best match that scenario to establish a whole new population of trees outside their current native range. A more conservative form of assisted migration involves strategic mixing of selected seed sources with local sources to increase diversity and adaptability to a range of future climates.

In forest plantation management, the genetics of planted trees is usually controlled by:

- selecting the geographic origin of seed sources and

- selecting genetic stock with superior traits of growth or other qualities (produced by tree breeding).

In the past, climate was assumed to be relatively static, and seed zones were proscribed to ensure that planted trees were adapted to local climate conditions. A genetic option for adapting forests to climate change is to relax geographic seed transfer rules based on static climate to optimize stand growth under a range of anticipated climate scenarios.

This approach is being developed and tested in the Pacific Northwest, particularly in British Columbia where temperature increases have been relatively large and climate-related impacts stimulate foresters to take action. Seed transfer rules have been revised to allow movement of southerly or lower elevation sources upward. A large-scale, assisted migration adaptation trial is under way testing 16 commercial tree species across 48 sites from Oregon to northern British Columbia.

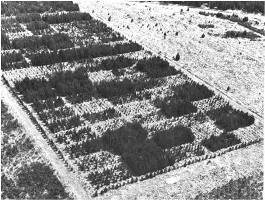

The practice of assisted migration may be greatly facilitated by decades of research on genetic variability and climate-related traits in provenance studies and tree breeding programs. Studies growing trees from seed sources collected across the species’ range in a variety of locations with different climate regimes allow us to examine climate-related traits and adaptability (common-garden studies). Provenance studies are ongoing for many of our major forest tree species.

Provenance studies show how some seed sources within a species native range perform much better than others, depending on the similarity of climate between the common-garden test site and the seed source location.

Related to Assisted Migration:

- The Debate about Assisted Migration

- Risk Management in Adaptation Strategies

- Adaptive Forest Management Strategies

- Biodiversity in Forests

- Invasive Species and Biodiversity

- Invasive Species and Climate