By Melanie Lenart, University of Arizona

Jon A. Krosnick, a political psychologist at Stanford University, pulled together results from various polls during his many years of social research to argue that most Americans believe in the existence and threat of climate change and have done so for over a decade.

Using findings from survey research he and his colleagues conducted since 1997, Krosnick explained during an hour-long presentation on April 19 at the University of Arizona that their research challenges some published claims about public beliefs. For instance, the research belies statements in the February 2011 issue of The Economist, which asked “Why don’t Americans believe in global warming?” and a November 2010 story in Bloomberg Businessweek stating “The number of Americans who agree the earth is warming because of man-made activities has been in free fall.”

What Americans Really Think About Climate Change

What Americans Really Think About Climate Change

The percentage of Americans who believe global warming has been happening went from about 79% in 1997 to 83% in 2011, he reported (Figure 1, Krosnick and MacInnis, 2011).

“These are large majorities,” he added, referring to all the polls of a randomly selected cross-section of Americans.

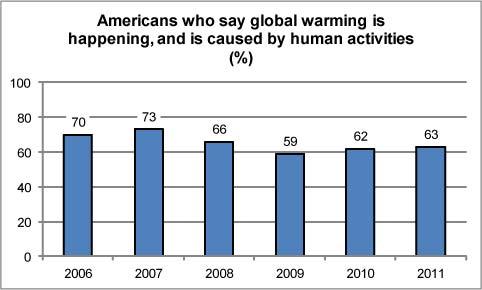

Taking into account answers to a question about the causes of warming, large majorities have said they both believed in warming and attributed it to human activities(Figure 2, Krosnick and MacInnis, 2011).

“There’s plenty of room here for increases in certainty,” though, Krosnick said. Results indicate roughly a third of Americans are “extremely sure” or “very sure” that global warming has been happening and

is caused by human activities, ranging from 27% to 39% from 2006 through 2011.

Despite claims sometimes made, convinced skeptics make up a very small proportion of the U.S. population, he noted. Typically less than a tenth of Americans have been “extremely sure” or “very sure” that it is not happening, ranging from 4% to 11% from 2006 through 2011.

In polls he and his colleagues administered between 2006 and 2010, roughly two-thirds of the American public said that the federal government should do more to deal with global warming since 2006, he reported. Even the lowest proportion supporting this since 2006, 56% in 2009, was higher than the proportions supporting this in 1997 (49%) and 1998 (47%). In these polls, about 84% or more of Americans have supported providing tax breaks to produce alternative energy.

Typically, he and his colleagues found that about 80% of Americans supported providing tax breaks to businesses or requiring businesses to take the following actions:

- reduce greenhouse gas emissions;

- build more efficient cars;

- build more energy-efficient buildings; and

- build more efficient appliances.

Krosnick said when he shared the polling results with members of Congress and their staff, he invariably heard that their constituents were “different” from the rest of the nation and more skeptical of climate change. So Krosnick decided to test whether individual states might have different profiles than the nation as a whole. To test this, his research team combined results from polls taken during different years to yield samples large enough to consider how opinions divide in individual states.

“In no state did we find a majority on the skeptical side,” Krosnick said. In the 50 individual states, 66% to 99% of residents polled said that global warming is happening, he reported, while 64% to 99% agreed it was happening and attributed its occurrence largely to human activities.

The political psychologist and his team also adapted the classic question, “What is the most important problem facing this country today?” This question, first asked in Gallup polls in the 1930s, found recently that the economy was the biggest issue on people’s minds, while global warming was rarely if ever mentioned.

To consider how much phrasing might matter, his team rephrased the question in this way: “What will be the most important problem facing the world in the future if nothing is done to stop it?” When asked this way, he said, “Global warming comes out in first place, not in last place (Yeager et al., 2011).”

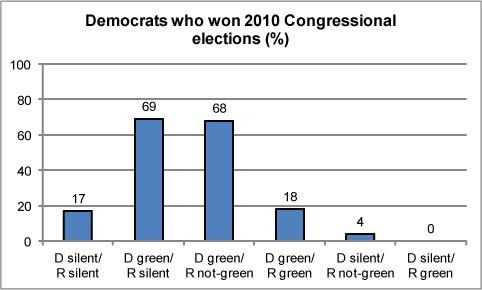

In another effort, the researchers did a comprehensive analysis of the official websites of candidates participating in the 2010 congressional election to test whether expressing green views helped or hurt candidates (Krosnick et al., 2011). They used candidates’ public statements to categorize whether they had taken a “green” or a “not-green” position on climate change, or expressed no views on the issue. As shown in Figure 3, Democrats who had expressed green positions on climate change were far more likely to win elections than those who remained silent or expressed “not-green” views.

“What if the Democrat says nothing and the Republican goes green? There are some instances of that,” he said. “Does that help the Republican? And the answer is: Absolutely. Not a single Democrat won in those situations where the Republican was the green candidate.”

Krosnick summed up by coming back to the question of why politicians remain reluctant to take action on climate change, despite majority support for such efforts.

“The starting question was, ‘Why no action?’ And what I hope I’ve shown you is that I don’t think you can blame the public. It looks like the public is pretty much where it needs to be to justify government action.”

References Cited

Krosnick, J.A., and B. MacInnis. 2011. National Survey of American Public Opinion on Global Warming. Stanford University with Ipsos and Reuters. Available online at http://woods.stanford.edu/docs/surveys/Global-Warming-Survey-Stanford-Reuters-September-2011.pdf

Krosnick, J.A., B. MacInnis, and A. Villar. 2011. The impact of candidates’ statements about climate change on electoral success in 2010: experimental evidence. Woods Institute Report. Stanford University. Available online at http://woods.stanford.edu/docs/surveys/Stanford_Climate_Politics2011.pdf

Yeager, D.S., S.B. Larson, J.A. Krosnick, and T. Tompson. 2011. Measuring Americans’ Issue Priorities: a new version of the most important problem questions reveals more concern about global warming and the environment. Public Opinion Quarterly. Vol. 75(10): 125-138.

External Links

Podcast of Krosnick Presentation at the University of Arizona, April 19, 2012

Jon A. Krosnick and Colleagues Survey Research on Climate Change and American Public Opinion

Related Articles

- Unraveling Public Perceptions on Climate Change

- Climate: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly

- Interpreting Climate Data for Land Management